|

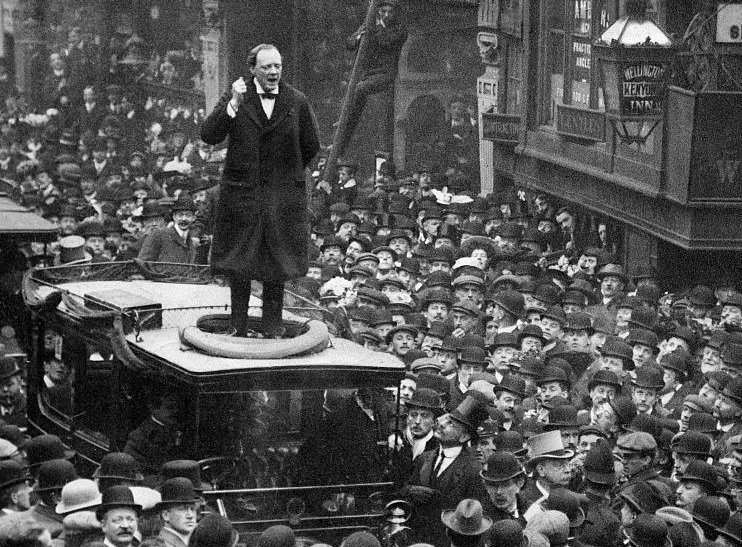

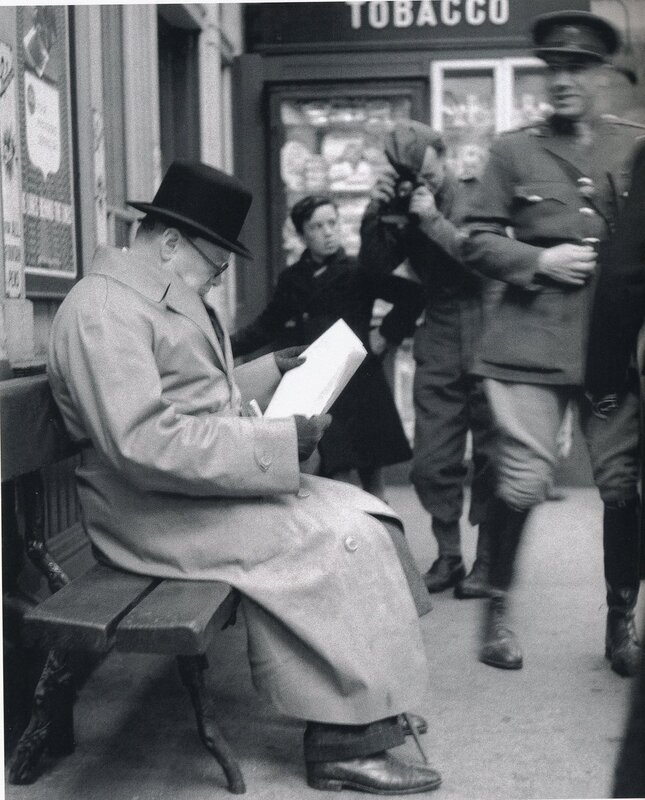

Who was Winston Spencer Churchill? Mark Milke, president of the Sir Winston Churchill Society of Calgary, with notes from Sebastian Voermann and David Holmes Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was a British politician whose storied career in public life spanned over six decades. Born in 1874, young Churchill’s early life was spent in the height of Victorian England, as the British Empire approached its apogee. After graduation from the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1895, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars, seeing action in India and Sudan. After resigning his commission in 1899, his electoral attempt for parliament that year ended in failure. On the outbreak of the Second Boer War, he went to South Africa as a news correspondent embedded with the army, greatly increasing his profile with the British Public. Elected to Parliament in 1900 at the age of 25, Churchill would serve in progressively more senior roles with both the Liberal and Conservative governments of the early 20th century. As the storm clouds of war drew nearer throughout the 1930s, Churchill was an early voice in warning against the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, and a passionate critic of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policies. By 1940, with war having arrived and the invasion of Britain a very real threat, Churchill rose to the Premiership as leader of a wartime coalition with the opposition Labour and Liberal Parties. His leadership throughout the war would prove key as the Allies defeated the Axis powers in 1945. His resoluteness has come to be seen as an enduring symbol of British and Allied determination. He was closely involved in foreign policy throughout the war, bringing together such disparate figures as Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin in their common cause against fascist tyranny. The Conservatives were defeated by Labour in an election weeks after V-E Day, but Churchill would return for a further four years in office from 1951-1955. Churchill died at the age of 90 in 1965 and was given a state funeral, the last time such a funeral was given for a non-Royal. Source: Britanica.com and the BBC. |

Connection to Canada and details about Churchill’s 1929 visit to Alberta |

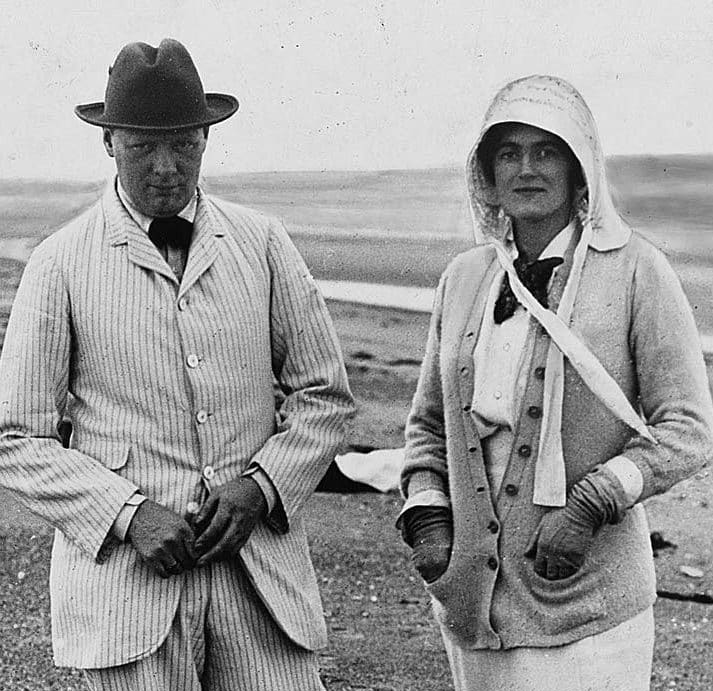

“Twenty Switzerlands rolled into one” was how Churchill described Alberta and its Rocky Mountains as he toured the province in 1929. As the former Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative government of Stanley Baldwin, his visit to Western Canada was a significant event at a time where Canada was evolving in its role within the interwar British Empire.

Following stops in Eastern Canada, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Churchill arrived in Edmonton along with his son, brother and nephew to be hosted at Government House by Lieutenant-Governor William Egbert. After departing the provincial capital, he was welcomed to the burgeoning 70,000-strong city of Calgary by Mayor Frederick Ernest Osborne on August 24 at the Canadian Pacific Railway depot. Meeting with the leading citizens of the young city, Churchill then embarked south on a tour of the oilfields in the Turner Valley area, and was reportedly extremely impressed by the development of the industry that would come to define Alberta’s economy in the succeeding decades.

Churchill then spent some days at the ranch of his friend the Prince of Wales (later, briefly, King Edward VIII), located in the foothills near Pekisko. From there, it was back to Calgary for a speech at the CPR’s Palliser Hotel on 9th Avenue, organized with the help of Canadian federal Conservative leader (a Calgarian, and soon to be Prime Minister) R.B Bennett. The Daily Herald reported that all in attendance “gained a new conception of the remarkable qualities and virtues which have produced one of the most outstanding statesmen in the British Empire.”

Several more days of relaxation in the Rocky Mountains, including at the CPR’s Banff Springs Hotel, concluded Churchill’s visit to Alberta nearly one hundred years ago. It is clear that he left with a strongly positive impression of Alberta’s natural beauty, the rapid development of its industries, and the energy of its people.

Source: Bradley P. Tolppanen, Churchill in North America, 1929. Jefferson, N.C.: MacFarland, 2014.

Following stops in Eastern Canada, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Churchill arrived in Edmonton along with his son, brother and nephew to be hosted at Government House by Lieutenant-Governor William Egbert. After departing the provincial capital, he was welcomed to the burgeoning 70,000-strong city of Calgary by Mayor Frederick Ernest Osborne on August 24 at the Canadian Pacific Railway depot. Meeting with the leading citizens of the young city, Churchill then embarked south on a tour of the oilfields in the Turner Valley area, and was reportedly extremely impressed by the development of the industry that would come to define Alberta’s economy in the succeeding decades.

Churchill then spent some days at the ranch of his friend the Prince of Wales (later, briefly, King Edward VIII), located in the foothills near Pekisko. From there, it was back to Calgary for a speech at the CPR’s Palliser Hotel on 9th Avenue, organized with the help of Canadian federal Conservative leader (a Calgarian, and soon to be Prime Minister) R.B Bennett. The Daily Herald reported that all in attendance “gained a new conception of the remarkable qualities and virtues which have produced one of the most outstanding statesmen in the British Empire.”

Several more days of relaxation in the Rocky Mountains, including at the CPR’s Banff Springs Hotel, concluded Churchill’s visit to Alberta nearly one hundred years ago. It is clear that he left with a strongly positive impression of Alberta’s natural beauty, the rapid development of its industries, and the energy of its people.

Source: Bradley P. Tolppanen, Churchill in North America, 1929. Jefferson, N.C.: MacFarland, 2014.

|

Churchill the social reformer

Winston Churchill was an early social reformer in addition to his later more well-known role as a wartime leader. Churchill was a passionate opponent of socialism but that opposition was not akin to opposing social and legislative reforms that would benefit the poor. (Churchill opposed socialism as the wrong means to the proper end of helping the poor.) One significant area of social reform supported by Churchill early on was labour legislation. As President of the Board of Trade in the government of Henry Asquith, he played an important early role in shaping the Trade Boards Act of 1909, introducing reforms including the minimum wage, the National Insurance Act of 1911, and support and advocacy for social insurance. In the early 1920s, he supported the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1920, which extended unemployment benefits to an expanded number of Britons. In his second premiership from 1951 to 1955, Churchill supported the Family Allowances and National Insurance Act, introduced by his government in 1952, provided expanded financial support for families. Sources: Hillsdale College and Centerpiece. |

Churchill and modern-day criticism

In recent years, Winston Churchill has come under attack from some who either properly characterize his positions such issues as imperialism (he was an imperialist), which has fallen out of favour, or wrongly blaming him as being responsible for the tragedy of the Bengal famine in India.

Entire debates have been held and books written on the above, the breadth of such discussions being beyond the scope of this essay. Instead, for those interested in following up on such topics, we offer below some brief thoughts and further reading.

Imperialism has been “out of vogue” since the early and mid-20th century, especially with U.S. president Woodrow Wilson’s notion of national self-determination post-World War One as being preferable to empires. Prior to that war, the “working assumption” was that empires were just another form of government, just as people could organize and/or be subject to governing entities such as tribes, city-states, principalities, or nation-states. The debate over the worth of this or that governance structure is beyond the scope of the Sir Winston Churchill Society of Calgary. We offer up the above as useful context for how leaders in democracies and non-democracies thought one century previous and before.

Useful reading on this topic includes a classic anti-imperialism text from Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism. A more sympathetic account of imperialism comes from Niall Ferguson in Empire and in Civilization.

A useful and interesting book on the specific, real-world clash of Winston Churchill and Mohandas Gandhi over India and British imperialism can be found in Arthur Herman’s Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Modern Age.

In recent years, Winston Churchill has come under attack from some who either properly characterize his positions such issues as imperialism (he was an imperialist), which has fallen out of favour, or wrongly blaming him as being responsible for the tragedy of the Bengal famine in India.

Entire debates have been held and books written on the above, the breadth of such discussions being beyond the scope of this essay. Instead, for those interested in following up on such topics, we offer below some brief thoughts and further reading.

Imperialism has been “out of vogue” since the early and mid-20th century, especially with U.S. president Woodrow Wilson’s notion of national self-determination post-World War One as being preferable to empires. Prior to that war, the “working assumption” was that empires were just another form of government, just as people could organize and/or be subject to governing entities such as tribes, city-states, principalities, or nation-states. The debate over the worth of this or that governance structure is beyond the scope of the Sir Winston Churchill Society of Calgary. We offer up the above as useful context for how leaders in democracies and non-democracies thought one century previous and before.

Useful reading on this topic includes a classic anti-imperialism text from Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism. A more sympathetic account of imperialism comes from Niall Ferguson in Empire and in Civilization.

A useful and interesting book on the specific, real-world clash of Winston Churchill and Mohandas Gandhi over India and British imperialism can be found in Arthur Herman’s Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Modern Age.

Churchill and anti-racism

As historian Andrew Roberts has noted, whatever one thinks of Churchill’s occasional but infrequent prejudicial words, there are contrary statements and actions. Over lunch in July 1944 with Indian statesman Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar, “Churchill was heard assuring him that the old notion that the Indian was in any way inferior to the white man must disappear. ‘We must all be pals together,’ the prime minister declared. “I want to see a great shining India, of which we can be as proud as we are of a great Canada or a great Australia.’”

We also have Churchill’s words and deeds that are anti-racist and which should also be remembered. Churchill argued that South African blacks should be given legal equality with whites. During the Second World War, Churchill refused an American military request to segregate black American military personnel in British establishments such as restaurants and pubs. Churchill also fought a common prejudice of his era, anti-Semitism, his entire political life.

Specific to Indians, as Andrew Roberts, and Zewditu Gebreyohanes have written, “Churchill was also a supporter of Indian rights in South Africa from very early on, even when this was opposed by his contemporaries, for which he was seen as a radical….[Mahatma] Gandhi would later praise Churchill for having stood up for Indians’ rights in South Africa in 1906.” Churchill also consistently boasted about the population increase in India under British rule.

Perhaps the most obvious example of Churchill’s opposition to racism is his leadership against Nazi Germany before and during the Second World War. He was an early and outspoken critic of Hitler’s rise to power, as well as the racist Nuremberg Laws that began targeting Germany’s Jewish population in the mid-1930s.

The Bengal famine accusations

The Bengal famine of 1943-44 killed over two million in the Bengal province of then-British India, as a result of a combination of local government mismanagement, natural disasters, and massive inflation which was caused in part by the Japanese invasion of neighboring Burma which ravaged the food supply.

Specific to charges that Winston Churchill or the British government was responsible for the Bengal famine in the Second World War, the charges are false.

Sources: Zareer Masani, “Churchill and the Genocide Myth”; Andrew Roberts and Zewditu Gebreyohanes, “ ‘The Racial Consequences of Mr Churchill’: A Review”.

Summary and books about Winston Churchill

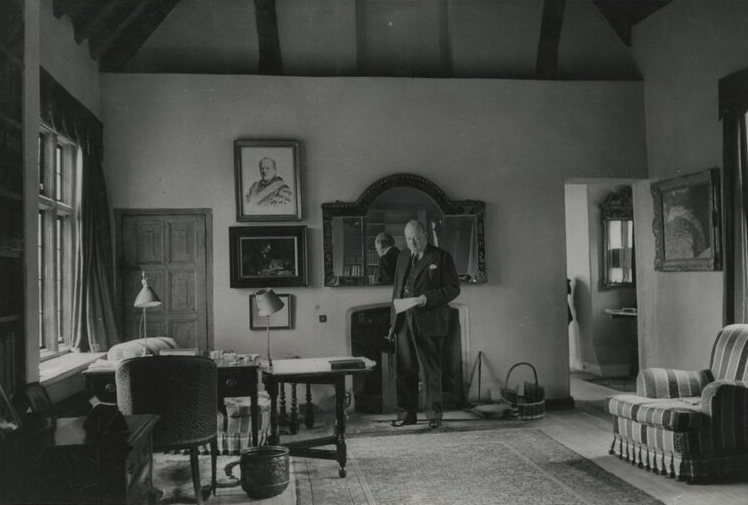

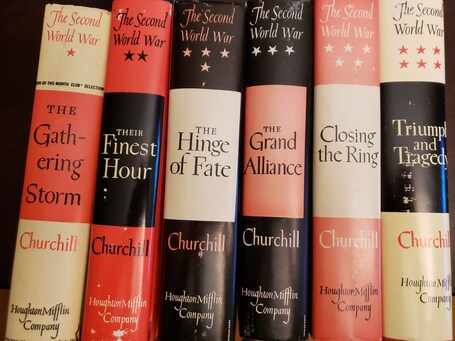

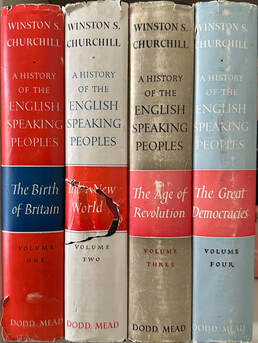

Over 1,000 books have been published on the life of Sir Winston Churchill in addition to his own books written during his lifetime including six volumes on the Second World War and even on the subject of painting, Painting as a Pastime. Churchill’s official biographer was Sir Martin Gilbert, who authored a plethora of books on the late British Prime Minister. Sir Gilbert’s most famous book is Churchill: A Life.

As historian Andrew Roberts has noted, whatever one thinks of Churchill’s occasional but infrequent prejudicial words, there are contrary statements and actions. Over lunch in July 1944 with Indian statesman Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar, “Churchill was heard assuring him that the old notion that the Indian was in any way inferior to the white man must disappear. ‘We must all be pals together,’ the prime minister declared. “I want to see a great shining India, of which we can be as proud as we are of a great Canada or a great Australia.’”

We also have Churchill’s words and deeds that are anti-racist and which should also be remembered. Churchill argued that South African blacks should be given legal equality with whites. During the Second World War, Churchill refused an American military request to segregate black American military personnel in British establishments such as restaurants and pubs. Churchill also fought a common prejudice of his era, anti-Semitism, his entire political life.

Specific to Indians, as Andrew Roberts, and Zewditu Gebreyohanes have written, “Churchill was also a supporter of Indian rights in South Africa from very early on, even when this was opposed by his contemporaries, for which he was seen as a radical….[Mahatma] Gandhi would later praise Churchill for having stood up for Indians’ rights in South Africa in 1906.” Churchill also consistently boasted about the population increase in India under British rule.

Perhaps the most obvious example of Churchill’s opposition to racism is his leadership against Nazi Germany before and during the Second World War. He was an early and outspoken critic of Hitler’s rise to power, as well as the racist Nuremberg Laws that began targeting Germany’s Jewish population in the mid-1930s.

The Bengal famine accusations

The Bengal famine of 1943-44 killed over two million in the Bengal province of then-British India, as a result of a combination of local government mismanagement, natural disasters, and massive inflation which was caused in part by the Japanese invasion of neighboring Burma which ravaged the food supply.

Specific to charges that Winston Churchill or the British government was responsible for the Bengal famine in the Second World War, the charges are false.

- In historian Zareer Masani’s article Churchill and the Bengal Famine, Masani characterizes claims of Churchill or British responsibility or non-action as a “myth” and notes that more than a million tons of grain in fact arrived in Bengal due to the efforts of Churchill and others.

- Indian economist Amartya Sen, Indian economic historian Tirthankar Roy, scholar Arthur Herman and historians Andrew Roberts, and Zewditu Gebreyohanes, among others have also addressed the Bengal famine accusations, found them false, and in addition addressed questions of racism vis-a-vis Churchill.

- First, Churchill was swift in coordinating and approving rice shipments to Bengal from all corners of the Empire, despite the threat and logistical challenges posed by the Japanese occupation of South-East Asia. This included arranging the shipment of 150,000 tons of wheat and barley from Iraq and Australia almost as soon as his cabinet was informed of the severity of the famine in August of 1943.

- Churchill appointed Sir Archibald Wavell as Viceroy of India in 1943, who is widely seen as a great improvement from his predecessor. Wavell is credited for deftly coordinating relief measures, implementing policies to mitigate the social impact of the tragedy, and effectively distribute food supplies to the affected population.

Sources: Zareer Masani, “Churchill and the Genocide Myth”; Andrew Roberts and Zewditu Gebreyohanes, “ ‘The Racial Consequences of Mr Churchill’: A Review”.

Summary and books about Winston Churchill

Over 1,000 books have been published on the life of Sir Winston Churchill in addition to his own books written during his lifetime including six volumes on the Second World War and even on the subject of painting, Painting as a Pastime. Churchill’s official biographer was Sir Martin Gilbert, who authored a plethora of books on the late British Prime Minister. Sir Gilbert’s most famous book is Churchill: A Life.

Below is an excerpt from Sir Martin Gilbert’s preface to Churchill: A Life as it is a useful, succinct, three-summary paragraph of the life and accomplishments of Sir Winston Churchill:

"Churchill’s involvement in public life spanned more than fifty years. He had held eight Cabinet posts before he became Prime Minister. When he resigned from his second Premiership in 1955 he had been a Parliamentarian for fifty-five years. The range of his activities and experiences was extraordinary. He received his Army commission during the reign of Queen Victoria, and took part in the cavalry charge at Omdurman. He was closely involved in the early development of aviation, learning to fly before the First World War, and establishing the Royal Naval Air Service. He was closely involved in the inception of the tank. He was a pioneer in the development of anti-aircraft defence, and in the evolution of aerial warfare. He foresaw the building of weapons of mass destruction, and in his last speech to Parliament proposed using the existence of the hydrogen bomb, and its deterrent power, as the basis for world disarmament.

“From his early years, Churchill had an uncanny understanding and vision of the future unfolding of events. He had a strong faith in his own ability to contribute to the survival of civilisation, and the improvements of the material well-being of mankind. His military training, and his natural inventiveness, gave him great insight into the nature of war and society. He was also a man whose personal courage, whether on the battlefields of Empire at the turn of the century, on the Western Front in 1916, or in Athens in 1944, was matched with a deep understanding of the horrors of war and the devastation of battle.

“Both in his Liberal and Conservative years, Churchill was a radical; a believer in the need for the State to take an active part, both by legislation and finance, in ensuring minimum standards of life, labour and social well-being for all citizens. Among the areas of social reform in which he took a leading part, including drafting substantial legislation, were prison reform, unemployment insurance, State-aided pensions for widows and orphans, a permanent arbitration machinery for labour disputes, State assistance for those in search for employment, shorter hours of work, and improved conditions on the shop and factory floor. He was also an advocate of a National Health Service, of wider access to education, of the taxation of excess profits, and of profit-sharing by employees. In his first public speech, in 1897, three years before he entered Parliament, he looked forward to the day when the labourer would become ‘a shareholder in the business in which he worked’.

“At times of national stress, Churchill was a persistent advocate of conciliation, even of coalition; he shunned the paths of division and unnecessary confrontation. In international affairs he consistently sought the settlement of the grievances of those who had been defeated, and the building up of meaningful associations for the reconciliation of former enemies. After two world wars he argued in favour of maintaining the strength of the victors in order to redress the grievances of the vanquished, and to preserve peace. It was he who first used the word ‘summit’ for a meeting of the leaders of the Western and Communist worlds, and did his utmost to set up such meetings to end the dangerous confrontations of the Cold War. Among the agreements that he negotiated, with patience and understanding, were the constitutional settlements in South Africa and Ireland, and the war debt repayment schemes after the First World War.

“A perceptive, shrewd commentator on the events taking place around him, Churchill was always an advocate of bold, farsighted courses of action. One of his greatest gifts, seen in several thousand public speeches, as well as heard in his many broadcasts, was his ability to use his exceptional mastery of words, and love of language, to convey detailed arguments and essential truths; to inform, to convince, and to inspire. He was a man of great humour and warmth, of magnanimity; a consistent and life-long liberal in outlook; a man often turned to by successive Prime Ministers for his skill as a conciliator. His dislike of unfairness, of victimisation, and of bullying – whether at home or abroad – was the foundation-stone of much of his thinking.

“Churchill’s public work touched every aspect of British domestic and foreign policy, from the struggle for social reform before the First World War to the search for a summit conference after the Second. It involved Britain’s relations with France, Germany, the United States, and the Soviet Union, each at their most testing time. His finest hour was the leadership of Britain when it was most isolated, most threatened and most weak; when his own courage, determination, and belief in democracy, became at one with the nation.”

- From Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life, Heinemann, London, 1991